I’m late to the 2014 party and just finished (and loved) Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel. As usually happens when I finish a novel I love, I Googled the author for insights into her writing process and found this interesting snippet on The Millions:

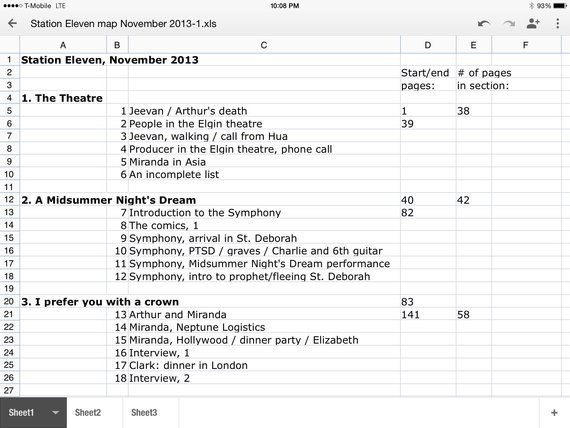

“I took a lot of notes as I was writing the book, and wrote out a detailed timeline. Later that wasn’t enough, so during the later revisions I put together a map of the book in Excel. This was in the final stretch, when I had the basic components of the novel and I was just rewriting and moving pieces around to try to find the best possible structure. The Excel map had notes on what was happening in each chapter, who had the point of view, the page count of each major section, etc. The book has an awful lot of moving parts, so I found the map invaluable in keeping track of everything. I was changing the order of chapters and sections right up until the end.” (Source)

“I took a lot of notes as I was writing the book, and wrote out a detailed timeline. Later that wasn’t enough, so during the later revisions I put together a map of the book in Excel. This was in the final stretch, when I had the basic components of the novel and I was just rewriting and moving pieces around to try to find the best possible structure. The Excel map had notes on what was happening in each chapter, who had the point of view, the page count of each major section, etc. The book has an awful lot of moving parts, so I found the map invaluable in keeping track of everything. I was changing the order of chapters and sections right up until the end.” (Source)

Much to my nerdy delight, there was a photo to accompany this snippet:

I love this type of insight into the enigmatic writing process. So many writers say that their stories “write themselves.” It’s like they are struck by some kind of artistic lightning and characters just come to life. Other writers say they methodically plan every scene of a story, paying close attention to plot points and character development.

Personally, I fall somewhere in the middle. The initial inspiration for a story is very mysterious to me. I just get ideas and I start writing and the voices of characters emerge. I rarely know how a story is going to unfold; I discover as I go and that’s what makes it fun for me. But, at the same time, while I’m discovering, I start jotting down notes of what I think can/should happen in upcoming chapters–a loose outline of sorts. By the end, I’m somewhat like Emily St. John Mandel, moving around chapters, making schematics of plot points and character developments.

A while back, there was an essay in Poets & Writers magazine called “Preparing for the Worst” by Benjamin Percy. I kept this essay on hand because I’m weird and I thought it was inspiring.

Percy wrote, “When I talk about the bloody business of writing fiction, I sometimes reference the act of mapmaking, blueprinting, planning out a story before beginning it. Often people find this either upsetting–‘You take the fun out of writing!’–or perplexing. ‘How do you graph a story? What is a beat sheet? When and why do certain actions or emotional gateways need to occur in my narrative?'”

He goes on: “First of all, nothing needs to happen in your novel, but it can be helpful to point out some things that commonly do happen. There are no rules, but there are ‘rules,’ certain foundational truths that you should understand and master before breaking away from them, experimenting. Know the ‘rules’ before you ignore them.”

I think this is where outlines and mapping help. They show you the overall flow of the story. I don’t think it’s wise to start stories with these tools; that could lead to creative paralysis. But, when the first draft (the barf draft, I call it) is done, it can be really helpful to revisit the story with a critical eye and look at how the pieces of the puzzle are fitting together.

Percy’s right. Readers do expect certain things. They enjoy certain formulas and will find stories that deviate too much inherently disappointing. I used to resist this, thinking, “It’s not about the readers! It’s my story!” But, really, it is about the readers. If you’re publishing something, it is about the readers.

When I was editing People Who Knew Me, my editor realized the present-day story line (it goes back and forth between past and present) was lacking some urgency and drama, which is necessary to keep the reader’s interest. I was resistant to altering the story, but I did. And then I did a lot of “mapping” and moving things around to enhance the structure. The result? A MUCH better book.

Writing a novel starts with art–a unique vision, often mysterious in origin. And it ends with craft–tweaking and tinkering to make an objectively better experience for the reader. I was stuck defending the art of it for so long, but I’m much more appreciative of the craft now. My philosophy now is to let the words flow for the first draft, then go back and manipulate the words (and sentences and paragraphs and chapters). Art, then craft.

You are inspiring Kim!