Since receiving a round of fairly extensive edits on my book, I’ve been thinking a lot about how most of the books I read are probably very different from their first drafts. And that gets me thinking about the creation of art in general. If a writer is heavily influenced by an editor, is the book really “hers” anymore? Has some integrity been lost? Does it even matter? I mean, I’d venture to guess most of the published books out there are better than their first drafts (though this is subjective). But what’s on the shelf is not really a direct line of communication between the author and her readers. There are other people who have interrupted that transmission–for better or worse.

Speaking of this topic, my writer friend Meredith sent me this interesting New York Times article about the influence editor Gordon Lish had on Raymond Carver’s works. It’s absolutely fascinating. Basically, for much of the past couple decades, Gordon Lish has been telling people that he played a crucial role in the creation of the early short stories of Raymond Carver. He implied that the stories were much more his own than Carver’s. This is a big deal. Raymond Carver is renowned for his short stories. As a writer, it interests me to know how much of what I read in those stories is really from Carver’s brain.

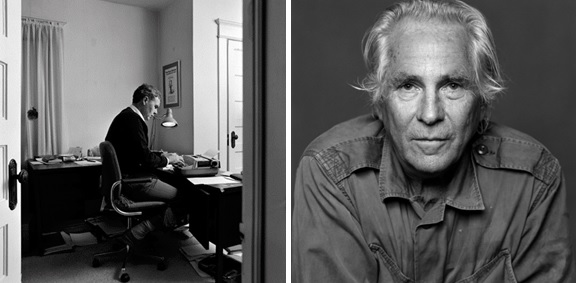

The author of the article, D.T. Max, visited the archives to look at the stories. He says:

“What I found there, when I began looking at the manuscripts of stories like ‘Fat’ and ‘Tell the Women We’re Going,’ were pages full of editorial marks — strikeouts, additions and marginal comments in Lish’s sprawling handwriting. It looked as if a temperamental 7-year-old had somehow got hold of the stories.”

Max sees a striking difference between Carver’s first two major collections and his later work. The early collections, which Lish edited, are “stripped to the bone. They are minimalist in style with an almost abstract feel. They drop their characters back down where they find them, inarticulate and alone, drunk at noon.” In contrast, the later two collections are “fuller, touched by optimism, even sentimentality.”

Some people say the discrepancies are related to Carver’s life: “The Carver of the early stories, it has been said, was in despair. As he grew successful, however, the writer learned about hopefulness and love, and it soaked into his fiction.”

Max wanted to investigate this premise by analyzing the edits. Here are some of his findings:

“There are countless cuts and additions to the pages; entire paragraphs have been added. Lish’s black felt-tip markings sometimes obliterate the original text. In the case of Carver’s 1981 collection, ‘What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,’ Lish cut about half the original words and rewrote 10 of the 13 endings.

In ‘Mr. Coffee and Mr. Fixit,’ for example, Lish cut 70 percent of the original words. With a longer story, ‘A Small, Good Thing,’ in which a couple anxiously wait for their child to come out of a coma, Lish cut the text by a third, eliminating most of the description — and all of the introspection. He retitled it ‘The Bath,’ altering the story’s redemptive tone to one of Beckettian despair. In Lish’s version, you no longer know if the child lives or dies.

Lish was constantly on guard against what he saw as Carver’s creeping sentimentality. In the original manuscripts, Carver’s characters talk about their feelings. They talk about regrets. When they do bad things, they cry. When Lish got hold of Carver, they stopped crying. They stopped feeling. Lish loved deadpan last lines, and he freely wrote them in: ‘The women, they weren’t there when I left, and they wouldn’t be there when I got back’ (‘Night School’). Other times, he cut away whole sections to leave a sentence from inside the story as the end: ‘There were dogs and there were dogs. Some dogs you just couldn’t do anything with’ (‘Jerry and Molly and Sam’). On occasion, Carver reversed his changes, but in most cases Lish’s handwriting became part of Carver’s next draft, which became the published story.”

By Max’s assessment, many stories were heavily influenced by Lish, to the point that they don’t seem like what Carver intended initially at all. But, again, I come back to my question: Does it even matter? If the goal is for people to read good stories, and if the edits by Lish make Carver’s stories arguably better, then is this a problem?

Even Max says, “Overall, Lish’s editorial changes generally struck me as for the better. Some of the cuts were brilliant, like the expert cropping of a picture. His additions gave the stories new dimensions, bringing out moments that I was sure Carver must have loved to see.” That, right there, is the crux of it. I think the editor’s job is to bring something out of the writer that the writer will point to and say, “Yep, that’s better.” It might not have been how the writer thought of it in the beginning, but I don’t think that’s bad.

Max goes to visit Lish, who says he doesn’t like to talk about the Carver period. He even says, “I can only be despised for my participation.” Lish has lots of enemies because of his editing style and the way it has called into question the purity of what’s published. I don’t know, I kind of feel bad for the guy. Carver got all the credit, all the awards, all the accolades. Lish thought of himself as “Carver’s ventriloquist.” Carver wasn’t blind to everything Lish did for him either:

“Responding to an edit in December 1969, Carver wrote: ‘Everything considered, it’s a better story now than when I first mailed it your way — which is the important thing, I’m sure.’ He echoed these sentiments in January 1971. ‘Took all of yr changes and added a few things here and there,’ he wrote, taking pains to add that he was ‘not bothered’ by the extent of Lish’s edit. Carver had a role in keeping the romance going, too. ‘You’ve made a single-handed impression on American letters,’ he wrote Lish in September 1977. ‘And, of course, you know, old bean, just what influence you’ve exercised on my life.'”

But, over time, Carver began to take issue with Lish’s editing:

“He wrote a five-page letter in July 1980 telling Lish that he could not allow him to publish ‘What We Talk About’ as Lish had edited it. He wrote, ‘Maybe if I were alone, by myself, and no one had ever seen these stories, maybe then, knowing that your versions are better than some of the ones I sent, maybe I could get into this and go with it.’ But he feared being caught. ‘Tess has seen all of these and gone over them closely. Donald Hall has seen many of the new ones. .and Richard Ford, Toby Wolff, Geoffrey Wolff, too, some of them. How can I explain to these fellows when I see them, as I will see them, what happened?'”

(In the end, the collection was published as Lish wanted, and it received front-page reviews and lots of praise.)

Carver still pressed for more control. In August 1982, he wrote to Lish, “I can’t undergo [that] kind of surgical amputation and transplantation.” They ended their professional relationship and Carver went on to continued success. When ‘Cathedral’ was nominated for both a Pulitzer and a National Book Critics Circle Award, Carver wrote a letter to Lish in which he noted that the title story “went straight from the typewriter to the mail.”

I think that’s the goal for most writers–straight from typewriter (or printer) to mail. Somehow, that seems more pure to us. That seems more fulfilling and validating. There’s something uneasy about someone coming in and mucking up things (even if it’s for the better). You start to question your talents and, if you’ve had a couple glasses of wine, your overall purpose as a writer and human.

After much thought though, I tend to agree with Carol Polsgrove, a professor at Indiana University who has written about the archives and says:

“If you exalt the individual writer as the romantic figure who brings out these things from the depths of his soul, then, yes, the awareness of Lish’s role diminishes Carver’s work somewhat. But if you look at writing and publishing as a social act, which I think it is, the stories are the stories that they are.”

The influence of editors and publishers is inevitable. It just is. When my book hits shelves next year, it will be a lot different from its original draft. The heart of it is the same, but my editor has made many suggestions that have, I think, improved the flow of the story so it’s more enjoyable for my readers. That, in the end, is what’s most important.

>> Read the whole D.T. Max New York Times article here