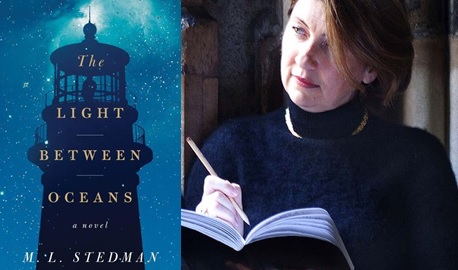

If you haven’t read The Light Between Oceans yet, I highly recommend adding it to your Amazon cart. It came out in 2012, so I’m a bit late to this particular party. Shameful confession: I’m never that excited to read historical fiction. I tend to think the characters are going to talk in their old-timey way and I’m not going to relate. I think I’ll fall asleep, basically. I’ve been wrong on this so many times, but I still have my ridiculous bias. This book may finally convince me to stop putting historical fiction novels at the bottom of my stack.

Usually, when I do these “spotlight on” posts, I choose authors who have written many novels that I’ve read and loved. This is the only M.L. Stedman book I’ve read. This is the only one she’s published (though, you better bet I’ll be first in line for her next one). I was so moved by this novel that I had to investigate Stedman’s writing process and compile some of her wisdom here.

On not sharing details of her personal life (including her first name):

“I like the reader to be free to inhabit fully the world of the book. I think that’s more difficult if the author is effectively standing between the reader and the story—a bit like making a movie and then standing in front of the screen. Promoting the author rather than the work is a fairly recent trend. As to using initials—there’s a very long and respectable history of writers of both genders doing so: T.S. Eliot, P.G. Wodehouse, C.S. Lewis, P.D. James, A.S. Byatt, J.D. Salinger… Things from ‘behind the curtain’ must surely affect readers’ experience, and more importantly, take them out of the story. Details of my life won’t shed any light on the book. Ultimately I think any novel should stand or fall on the words on the page. Every novel effectively begins with the appeal from the writer to the reader: ‘Imagine the following…’ For me, the key is ‘imagine.'” (Source)

“As the book’s not autobiographical, details of my life won’t really shed light on the story for the reader and I’d much rather let readers focus on the book and their own experience of it.” (Source)

On inspiration for the novel:

“I write very instinctively, letting a picture or phrase or voice come into my mind and just following it. For this story the setting turned up first—I closed my eyes and saw a lighthouse, then gradually a woman, and I knew it was a long time ago, on an island off Western Australia. Then a man appeared—the lightkeeper. As I wrote, a boat washed up, with a dead body and a crying baby, so I had to keep writing to see what happened. I didn’t consciously decide to write a book about lighthouses, but I found they provided an incredibly rich metaphor: They betoken binary opposites such as safety and danger, light and dark, movement and stasis, communication and isolation—they are intrinsically dynamic because they make our imaginations pivot between those opposites.” (Source)

On her writing process:

“There really isn’t such a thing as a ‘typical’ writing day for me, except insofar as I only write in the daytime—never at night. I’m rather allergic to rules about writing, and pronouncements such as ‘you must write at least an hour a day’ or ‘you must plot everything in advance’ or ‘do all your research before you write a single word.’ My philosophy is ‘find out what works for you, and do that: Everyone is different.’ So, for example, I wrote this book on my sofa, in the British Library, in a cottage by the beach in Western Australia, on Hampstead Heath, and anywhere else that felt right. I consider it a true privilege to have the opportunity to do what I love.” (Source)

On research:

“One of the few places where Australian WWI veterans “spoke” was in the field diaries and battalion journals written during and shortly after the war. Essentially private records rather than anything to be published commercially, they are truly heartbreaking to read—stories told without self-pity, facts recounted without commentary, and all the more devastating for that. I frequently found myself not just in tears but actually sobbing as I read them, in the otherwise orderly silence of the British Library reading rooms.” (Source)

“I visited the Leeuwin Lighthouse and the Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse, as well as spending time in the Australian National Archives going through the old log books and correspondence of the lightkeepers of the period. I also visited Trinity House in London, which is in charge of UK Lighthouses, and did a lot of research in the British Library. I wrote some of the book there, some of it on my sofa, and some of it in little cottages looking out over the Indian Ocean, down near where I imagine Point Partageuse to be. I found the research completely captivating, and an essential part of bringing that world to life for the reader.” (Source)

“My research very much followed the story rather than leading it.” (Source)

On writers who influence her:

“I’m not entirely sure what it means to say that I’ve been influenced by a writer—I hesitate lest it seem I’m claiming to be in their league. Writers I admire include Graham Greene, because of his beautifully honed prose and fascination with moral struggles; anyone who turns a beautiful sentence—like Cormac McCarthy, Marilynne Robinson, and Anne Michaels; and writers who know what makes people tick: Dickens, Eliot, Salinger.” (Source)

On not planning the story:

“I write ‘from the inside outward’ rather than ‘from the outside inward’, by which I mean that I know lots of people who build the scaffolding first, plotting out their story and structuring it, working it all out, and then sit down to put the bricks together. I never plan what I write – I wait for the story to unfold for me, without demanding to know where it’s going, and I make sense of it later. From the moment the boat washed up on the beach, I had to keep writing to see what happened next, as I had no idea who these people were. And I didn’t know how the story would end until it ended, because there were so many ways it could have gone. I think that has filtered through into the text, because I hear a lot from readers who say they just had no idea what was going to happen next, and kept reading into the wee small hours (one until 5am!) to find out.” (Source)

“I just sit down and make it up. I don’t plan, so it’s not as though I have an outline or structure. It’s an instinctive process. When I start to write I let a picture or sentence or voice come to me.” (Source)

On finding the story:

“The process was like walking into a dark room after having been out in bright sunlight: at first you see nothing and think the room is empty, then little by little, as your eyes adjust, things emerge from the shadows and you see what’s in there. For me, the trick is to stay, just stay. It can be tempting to say, ‘Oh, there’s nothing there,’ but in my experience, if you wait without expectation or demand, there’s always something there that will eventually let itself be seen.” (Source)

On letting characters guide the story:

“The story just emerged from nothingness, and I had no idea how it would end. Equally, until the very end of the book, I didn’t really have a sense of making ‘choices’ about the characters – they were who they were, they did what they did, and those actions carried with them certain consequences: more like physical laws of action and reaction. I felt deeply for them all – not just Tom and Isabel, but even the minor characters, and even when I disagreed with what they did in one circumstance or other.” (Source)

“I had no idea how the story would end until it ended: In one sense, it really could have gone any way. I loved having complete freedom to see where it wanted to go. Because I don’t plot, I didn’t have to contrive a way of getting to a given destination. Having said that, in some ways the ending arose simply from letting the characters be who they were – letting them play out their values and desires.” (Source)

On empathy:

“There’s a great deal to be said for that old expression ‘walk a mile in the other person’s shoes’, don’t you think? I believe that people are born with a strong instinct for good. Of course, views of what ‘good’ looks like differ wildly. But I think it’s usually possible to find compassion for even the most misguided of individuals: that’s different from condoning harmful behavior. It’s just recognizing that the business of being human is complex, and it’s easy to get things wrong. Compassion and mercy allows society to heal itself when we do.” (Source)

On her love of writing:

“I loved writing this book and remember at one stage wondering, ‘If I could do anything in the world, how would I be spending this day?’ The answer came back, ‘I would be doing exactly this.'” (Source)

On her advice to aspiring writers:

“Write because you love it. Write because that’s how you want to spend those irreplaceable heartbeats. Don’t write to please anyone else, or to achieve something that will retrospectively validate your choice.” (Source)

Fun facts:

- Stedman is a native Australian, but currently lives in London

- Her first name is Margot

- Stedman used to work as a lawyer

- The Light Between Oceans began as a 15,000-word short story

- There were NINE international bids on the novel–this is highly unusual for books by first-timers

- It’s reported that she procured a U.S. deal for “high six figures”–also highly unusual for first-timers

- The Light Between Oceans is currently being developed into a film by Dreamworks

A very involving, humane, and sensitive story for everyone in the world

Meaningful in many ways.

Read 4/06/24, Orlando, FL USA