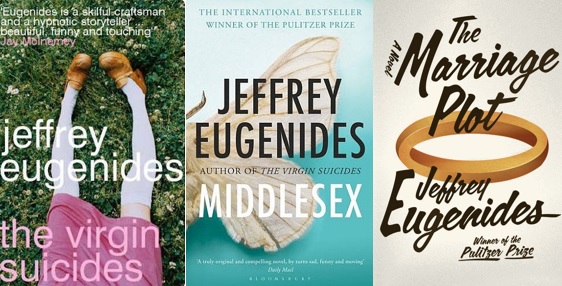

Jeffrey Eugenides is one of those writers who leaves my jaw on the floor every time. I consider him so far out of my league that envy isn’t even in the cards; just admiration and awe. Eugenides is a literary writer who is also popular–in other words, a rarity. He wrote The Virgin Suicides in 1993 (which became a movie), Middlesex in 2002 (which was an Oprah pick and won the Pulitzer Prize), and The Marriage Plot in 2011 (which should have won the Pulitzer Prize). His books are masterpieces. It’s no wonder they take years to come to fruition.

On deciding to be a writer:

“I decided very early—my junior year of high school. We read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man that year, and it had a big effect on me, for reasons that seem quite amusing to me now. I’m half Irish and half Greek—my mother’s family were Kentuckians, Southern hillbillies, and my paternal grandparents immigrants from Asia Minor—and, for that reason, I identified with Stephen Dedalus. Like me, he was bookish, good at academics, and possessed an ‘absurd name, an ancient Greek.’ Joyce writes somewhere that Dedalus sees his name as an omen of his destiny, and I, at the dreamy age of sixteen, did as well. Eugenides was in The Waste Land. My Latin teacher pointed that out to me. The only reason I was given to these fantasies in the first place, of course, was that the power of Joyce’s language and the story of Stephen Dedalus refusing to become a priest in order to take up the mantle of art were so compelling to me. Dedalus wants to form the ‘uncreated conscience of his race.’ That’s what I wanted to do, even though I didn’t really know what it meant. I do remember thinking, however, that to be a writer was the best thing a person could be. It seemed to promise maximum alertness to life. It seemed holy to me, and almost religious.” (Source)

On the origins of his stories:

“There is something deeply psychological and emotional that draws me to the material in the first place. It’s hard to explain. It’s the kind of thing you’d sit on a shrink’s couch for years trying to figure out.” (Source)

On first sentences:

“What I’m searching for with the first sentence is the entire book. They’ve come to me in different ways with the three books. And the process is not always the same, but finally there is a sentence that seems to suggest the entire narrative and the tone and the narrative strategy and everything all in one. That’s when I know essentially that I have a book that I can write.” (Source)

On editing:

“For me, it’s not that hard to throw away a year’s worth of work. My problem is throwing away things that I actually might be able to save, or things that I haven’t figured out how to improve. Throwing out too much is probably more my problem than not throwing away enough.” (Source)

“The fact that I’m working every day and publish so seldom shows that I’m reworking and rewriting a lot on the sentence level, and on the paragraph and structural levels, too.” (Source)

On how he plans (or doesn’t plan) his books:

“I don’t start with an idea and outline it. I don’t see how you can know what’s going to happen in a book or what the book is about beforehand. So I plunge in headlong, and after a while I get worried that I don’t know what I’m doing or where I’m going, so I begin to make a fuzzy outline, thinking about what might happen in the book or how I might structure it. And then that outline keeps getting revised. I’ll have it there, like a security blanket, to make me feel better about what I’m doing, but it’s provisional. Always you discover things and have ideas of how it might work out as you’re writing, and often the surprise of coming to these conclusions is what makes the book’s plot points surprising to the reader, too. If you can see on your first day what’s going to happen, the reader can likely guess as well. It’s the more complex ideas, the more difficult-to-foresee consequences of your story, that are more interesting to write about, and to read about as well.” (Source)

On the challenge of writing such big, epic novels:

“Well, one of the hardest things about writing Middlesex was trying to stay true to the original impulse. I felt young when I began the book but something more like middle-aged by the time I finished it. All sorts of life-altering things happened to me while I was writing it, too. My father died in a plane crash. I became a father myself. William H. Gass says it’s difficult writing a long book because as you go along, you get better, and then you have to go back and try to bring the rest of the book up to the same level. I did a lot of that. I obsessively went back and reworked the early parts of the book. Even so, I made sure the later chapters had the same voice and spirit as the early chapters.” (Source)

“I had this torture waiting for me every day, but at least it was my torture. The book was my jailer and we became friendly.” (Source)

On sacrifices of the writing life:

“The lucky thing is that writing has only made me sacrifice things I can get along without: a frisky social life, a manly feeling of being ‘out in the world,’ office gossip, teammates. You can be married and write. You can have a family and write. So you do have a life, after all. It’s waiting for you just outside your studio.” (Source)

On writing influences:

“Influence isn’t just a matter of copying someone or learning his or her tricks. You get influenced by writers whose work gives you hints about your own abilities and inclinations. Being influenced is largely a process of self-discovery. What you have to do is put all your influences into the blender and arrive at your own style and vision. That’s the way it happens in music—you put a sitar in a rock song and you get a new sound. It’s hybridization again. Hybrid vigor. It operates in art, too. The idea that a writer is a born genius, endowed with blazing originality, is mostly a myth, I think. You have to work at your originality. You create it; it doesn’t create you.” (Source)

On considering the reader:

“I tell my students that when you write, you should pretend you’re writing the best letter you ever wrote to the smartest friend you have. That way, you’ll never dumb things down. You won’t have to explain things that don’t need explaining. You’ll assume an intimacy and a natural shorthand, which is good because readers are smart and don’t wish to be condescended to. I think about the reader. I care about the reader. Not ‘audience.’ Not ‘readership.’ Just the reader. That one person, alone in a room, whose time I’m asking for. I want my books to be worth the reader’s time, and that’s why I don’t publish the books I’ve written that don’t meet this criterion, and why I don’t publish the books I do until they’re ready. The novels I love are novels I live for. They make me feel smarter, more alive, more tender toward the world. I hope, with my own books, to transmit that same experience, to pass it on as best I can.” (Source)

“I care about the reader, and I’m trying to keep the reader’s attention for as long as I can. I’m hopefully making the reader feel a lot about the characters and then about their own life. I want an ending that’s satisfying. I’m more of a classical writer than a modernist one in that I want the ending to be coherent and feel like an ending. I don’t like when it just seems to putter out. I mean, life is chaotic enough. One of the reasons that art is important to me is sometimes it actually feels more coherent than life. It orders the chaos.” (Source)

On where he writes:

“In college and in the apartments I lived in after college, I had just one room that was mine—my bedroom. So I’m used to working at a desk that’s not that far from the bed. I worked in the living room for part of Middlesex. Finally, when we moved to Berlin, we got a bigger apartment, and I worked in one of the extra bedrooms. Mainly I’ve written my books in bedrooms of apartments. This is the first house we’ve ever owned, so now I have an actual studio. I was almost fifty by the time I had one.” (Source)

“I have a very beautiful room in my house that we bought in Princeton. It’s glass on three sides, and you’d think that’s the perfect place to write. Somehow in that nice room I feel too exposed, and I can notice I’m too distracted by things going on, so I end up writing in a not-very-nice office bedroom. So sometimes you just want to go into a small space where you’re not distracted. I always work in a room where there’s no Internet to keep from being distracted so easily. A few years ago in Chicago, I rented an office, and I went there every day. For the most part I do work at home in an ugly room.” (Source)

“Leonardo said that small rooms concentrate the mind. I find that I like working in small, cramped rooms with not much in them, as compared to a pretty studio.” (Source)

On his writing routine:

“I try to write every day. I start around ten in the morning and write until dinnertime, most days. Sometimes it’s not productive, and there’s a lot of downtime. Sometimes I fall asleep in my chair, but I feel that if I’m in the room all day, something’s going to get done. I treat it like a desk job. With The Marriage Plot, the last year or so, I started doing double sessions where I would work all day, have dinner, and then go back and work at night. I didn’t want to put myself through that, but I had so much to do and a lot of things were coming together, so I had to work long hours. I’d go to bed at midnight and wake up at seven or eight and start again.” (Source)

“I spend most of every day writing. I like to write every day if I can. I don’t start extremely early. Richard Ford gets up at 6 in the morning and writes till midday. I tend to get up late and start at maybe 10 o’clock and work through the day until evening. And that schedule accords with family life, and, you know, I have a daughter. If I lived alone I think I might stay up later and start later in the day. But I sort of have to keep it like a professional job. Like a 9-to-5 job, but seven days a week.” (Source)

“[I] have breakfast and sit at my desk. It’s really very dull and simple. The German phrase sitzfleisch[the ability to sit in a chair and endure a task], it means you have a lot of meat on your behind. The person that has sitzfleisch can sit in the chair the longest. The Germans think this is very important for scholarship and for work in general. I agree that this is what you need for writing novels. It’s a long and slow haul, and there’s nothing about the process that is particularly interesting. I don’t have any special things I do, like a little stuffed animal that I stroke or a kind of potion that I drink. There’s nothing about it except the regularity of it.” (Source)

“You have to be very disciplined…you can’t wait around for inspiration. You have to just show up and hopefully it will happen.” (Source)

“I compose on the computer. Now and then, I print out what I’m working on and make handwritten corrections. There’s usually a period where I make corrections by hand, turn the page over, and write new paragraphs on the back of the sheet. I used to do that almost every day. It seems I do that less and less often. Now I can go as long as a month before printing something out. But there are always handwritten corrections at some point.” (Source)

On his writing rituals:

“The usual stimulants—coffee or tea. And at the end of a book, when I’m extremely exhausted, mentally fatigued, I sometimes sneak off into the yard and smoke a cigar, maybe six or seven times per book. That’s a bad habit I picked up when I lived in Berlin.” (Source)

On when he shares his work with others:

“Extremely late. Years and years go by without anyone seeing anything. I want my mistakes to become obvious to me before anyone else has to suffer reading them, so I never feel the need to show anything for a long time. Finally I do, but, for instance, The Marriage Plot was entirely written before my editor, Jonathan Galassi, read a word of it, except for the excerpt that was in The New Yorker. But I don’t know if it’s the most effective way to work. I think I’m so scared the book is going to be bad that I don’t want anyone to see it until I’ve fixed everything that can be fixed. And you can keep fixing things ad infinitum.” (Source)

On staying true to the love of writing:

“I do like to return to, or try to keep myself in, the original conditions I had when I began writing. That is, not being a professional, not thinking I’m writing a novel anyone is going to read, not realizing I’m being paid for it as part of any kind of commercial industry. Just a young guy, alone in his room, who wants to write something because of the excitement of it. Those are the conditions that I try to pretend exist around me.” (Source)

On criticism:

“Writers are quite aware of the flaws in their books. We know what we haven’t managed to do and what we’d like to do better the next time.” (Source)

On thinking about the critics:

“You become more self-conscious, I think, when you go on. When your book becomes a commodity, then you start to see it from different angles you would’ve never suspected. You realize it can be summed up in a few sentences and on the basis of those sentences, people will decide whether they want to read it or not. So you do start to imagine that when you write your next book. How will they describe this book?” (Source)

On self-doubt:

“[I’m] full of self-doubt and voices saying, ‘No, don’t do this. It’s terrible’… I’m constantly having doubts and moments of depression and then excitement and then back into the slough of despond.” (Source)

On setting aside projects:

“That happens to me all the time. Usually I get to a point where I think a book isn’t working, I get very anxious about it, and I have to put it away for a little while. In those gaps I usually start something new. Sometimes I think I’m starting something better, but then, of course, I write the new thing, and I see that’s also going to be difficult, and then I go back to the first one. I’m constantly doing that: shuffling between different projects. Maybe that will stop now at middle age, but that’s how it’s been so far.” (Source)

“I don’t publish everything I write. I must have six unfinished novels at least.” (Source)

On the non-fiction in fiction:

“I’m not really an autobiographical writer, though I use stuff from my life to make my stories seem real. But when I actually write about myself I get very confused. … You need to write about yourself in terms of how you feel and in terms of what you’ve seen, but when you put it into another character, you free yourself from having to be accurate and truthful. You can make a different kind of truth. Whereas if you write about yourself, there is an actual truth that you’re trying to get to that you can never get to. I think that people who write memoirs must constantly be fearing that they’re not saying the truth about what happened, but with a novel, whatever you say is true and I think is more true than memoir. You’re still putting your thoughts and beliefs about the world into the character but the facts don’t all have to line up.” (Source)

On short stories:

“Everyone starts with short stories. You have to learn how to write so you have to learn how to write on the smallest level possible…I find that it’s easier to write novels than short stories. My mind is naturally suited for long form. Stories are like training wheels on a bicycle for me.” (Source)

“It takes me forever to write short stories too! They’re even harder, in a way…I don’t have any firm principles when it comes to writing stories. Sometimes I think that the trick of writing a good story is to compress a novel’s worth of material into a short space. Other times, I think it’s best to present a small passage of time that is somehow representative of an entire life or situation. To keep my short stories properly short, lately I’ve been conceiving of them as poems. Long poems, where stuff happens. You want a maximum density of language and you want to leave out everything but the essentials.” (Source)

Fun facts:

- He was born in Detroit in 1960; Detroit shows up in his stories

- He got his undergraduate degree at Brown, where he became friends with writer Rick Moody

- He volunteered with Mother Teresa in India after graduating from college

- He got an M.A. in Creative Writing from Stanford

- He moved to New York in the eighties, where he befriended a fellow struggling writer, Jonathan Franzen

- His literary influences include Joyce, Proust, and Faulkner

- He started out as a poet; the first prize money he ever received from writing came from winning second place in a poetry contest

- He teaches writing at Princeton

- He says his next work will be a book of short stories

2 thoughts on “Spotlight on: Jeffrey Eugenides”